Preface

During an intensive week in June 2025, PhD students and faculty from C²DH, the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA) and Old Dominion University (ODU) converged on the beautiful Greek Island of Lesvos for a summer school at the Metochi Study Centre of the University of Agder.

Born out of a previous brainstorm meeting at the Metochi Study Centre in 2024, the summer school’s key goal was for the participating PhD candidates to collaborate on a joint project: The Lesvos Time Machine. Inspired by the European Time Machine initiative and the Luxembourg Time Machine project, this time machine project sought to promote team-building and interactional expertise.

As digital history revolves around collaboration and co-creation, the goal was not to deliver a finished product, but to give students a taste of what it means to jointly develop, plan, and execute a project with a highly diverse group of students, whether in terms of interests, background, and academic training.

With this in mind, students began the week by collaborating in smaller groups to explor the island in search of historical evidence (“data”) about its rich past. Lesvos has a UNESCO World Heritage classified “Petrified Forest”, great architectural heritage and historic landscapes, numerous smaller museums, and important monasteries with medieval manuscripts.

Their “challenge” was to map, collect, curate, and manage that data to produce a “Lesvos Time Machine” that would allow future visitors to discover the history of Lesvos in a playful, interactive, and digital manner. This, of course, was an exercise that asked for careful coordination of group activities, creative co-design sessions, and plenty of discussion, spontaneity and problem-solving spirit in order to realize a common goal. In the end, the participants all came away with new friendships and a taste for the promise of digital history.

Six participants were invited to comment on their experiences at Lesvos: two from the C²DH, two from NKUA, and two from ODU. The first three take a broader outlook on their time in Lesvos while the later three take a narrower view, concentrating on the process of producing a pilot project for the Lesvos Time Machine.

Author: Gerben Zaagsma

Professor, C²DH, University of Luxembourg.

Author: Apostolos Spanos

Professor, Department of Religion, Philosophy and History, University of Agder.

Author: Andreas Fickers

Director, C²DH, University of Luxembourg.

Processes

At the outset, our Lesvos Time Machine project embraced one wish: make accessibility part of the process, not a check-in-the-box afterthought. Here, accessibility has two dimensions. The first is ability-based inclusion, ensuring that users with permanent, temporary, or situational disabilities can perceive, access, navigate, and contribute to the archive. The second is spatial inclusion, which recognizes that physical or virtual entry often hinges on the social capital of local knowledge holders who guide others to the “door” of tradition, culture, and people who call this island home. It seems like a tall order for a short, “one wish,” request but really, it boils down to making it possible for a wide array of people to be included in the ways we learn and participate in history.

Translating that ambition into praxis across a 30+ person cohort spanning over 18 countries demanded shared guardrails. Our accessibility & inclusion subgroup kept those guardrails in view by treating inclusive design as a core conviction. We developed a living WCAG-inspired manifesto that instantiates a process for iterative assessment of accessibility adapted to archival use. In a future version of this time machine, local knowledge holders can play a key role in bridging local access, maintain cultural nuance, and evaluate assistive technology relevance. As the time machine is still under construction, this manifesto of accessibility, anchored by community liaisons who bridge both abilities and place, ensures that each iteration extends access rather than narrows it.

Author: Mel-Miller-Felton

PhD Candidate, International Studies, Old Dominion University.

Working in such a big group made collaboration difficult at first. It took time to agree on where to store our data, how to set up categories, and what information needed to be tagged. We all came to the summer school with different levels of technical knowledge and we all learned as we worked together. We learned from each other and, over time, the process became more balanced. Our team worked on data entry, but we were not just performing a task. We were shaping how we thought about structure, access, and meaning.

It also raised important questions. What counts as useful data? Who defines the categories? How much interpretation is allowed when building a system others will rely on? These conversations kept coming up, and they weren’t abstract. They affected every step.

One of the moments that stayed with me was being in the Metochi Study Center library, labeling our data together. It was quiet, steady work. It felt thoughtful. It also felt collective. For something that usually stays behind the scenes, data entry carried more meaning than I expected.

Author: Spyridoula Spyridon

PhD Candidate, HPS, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

As readers already know, from our first day at the Summer School in Lesvos we were tasked with building a time machine for the island. Initially unsure of what this would look like, we went through the Time Machine Organization’s website and discovered different approaches and projects that all mapped “European social, cultural and geographical evolution across time”. But what would it mean concretely for one of the most historically dense islands in the Aegean, and our limited timeframe of just… six days?

Coming from diverse backgrounds meant our visions were very different, and it was only after long debates that we agreed that our time machine would be a historical game. Engaging yet instructive. Historically grounded yet playable.

The two first days of the summer school were dedicated to data collection: we were set loose in different parts of the Island, collecting photographs, videos, oral testimonies, and even Santouri recordings. We returned with rich but scattered data. The first step was to centralize all of this in a database designed with PostgreSQL, structured via DBeaver, and mapped with QGIS, linking each piece of collected content to a place, a time, and a description.

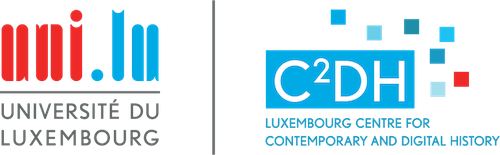

We then experimented with LLMs (ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini) to generate visual storyboards and pixel-art sprites. When we had real imagery (interviewed locals or iconography of historical figures such as the famous local poet Sappho) we prompted the models based on these. For figures lacking visual records (such as the monk Agathon of Agiasos) the AI generated plausible likenesses based on contextual description. While these assets accelerated our workflow, we were not unaware of the biases and speculative leaps that AI can embed.

Finally, two Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)-based chatbots completed the prototype: the first provided image description and the second served as a “history instructor,” designed to respond to learners in context.

At the end what we conceived was not a final product, but an experimental artifact. Our Lesvos Time Machine remains provisional, but perhaps that is the point: not to offer closure but to invite interrogation, on the stories we select, the data structures we impose, the AI-driven assets we generate. Interrogations that are not unfamiliar to the field of digital history itself, nor to those of us who discovered that the true time machine was the friends (and the shared folders) we made along the way.

Author: Ferdaous Affan

PhD Candidate, D4H, C²DH, University of Luxembourg.

Participants

Participating in the summer school in Lesvos as a student from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA) was a unique and sometimes demanding experience. What struck me most was the diversity of academic backgrounds and the challenge of working together across disciplines. Participants came from very different disciplinary cultures. On the one hand, there were those working in philosophy, history, and the social sciences while, on the other, there were those with backgrounds in computer science, digital humanities, and technical development. Finding a common ground between these approaches was intellectually stimulating and at times difficult. The open-ended nature of our research process in Lesvos gave us the freedom to explore themes that mattered to us personally, but it also exposed how methodological differences can lead to disagreement. These disagreements often stemmed from different ways of approaching and thinking about knowledge, making collaboration both challenging and thought-provoking. It reminded us that knowledge is never neutral, nor is it purely objective, it always shaped by shared perspectives, values, and interpretations. That, to me, is what made our shared experience meaningful.

Even though our NKUA group was small, we contributed in meaningful ways, especially through language mediation and local knowledge since we were the only Greek-speakers at the summer school. Beyond translation, our familiarity with the cultural and historical landscape of Lesvos helped situate broader conversations in context. The presence of Greek-informed and philosophy-oriented perspectives also added a theoretical grounding to discussions, especially on issues of method, positionality and ethics. I brought a feminist and queer lens to our interviews and reflections. This helped bring gender dynamics to the surface, even if did make other conversations with locals delicate.

Lesvos offered a complex and moving context, from local folk traditions to the realities of refugee life. I was grateful to be part of the data entry group, where a shared approach created a supportive and productive environment. As a group, we were able to bring together our individual insights and create something collaborative and thoughtful. I left the week feeling both challenged and enriched.

Author: Maria Amiridi-Wiedenmayer

PhD Candidate, HPS, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

As the newest member of the D4H I’ve had an interesting experience reflecting on our institute’s experience during the Metochi Summer School on Lesvos. On the one hand, we were the organizers of the summer school; on the other hand, this experience was so much more than our institute. At first, I wanted to use this opportunity to get to know my D4H colleagues. In the end, however, I was also able to make new friends from different universities.

Building a time machine for Lesvos over the course of one week was an ambitious project, especially considering the great work of other time machine projects before us, and the diverse academic backgrounds of the participants amplified this. In the D4H, we’re no strangers to interdisciplinary collaboration, because we’re already from different backgrounds and institutes of the University of Luxembourg. Some of us are historians, while others are computer scientists, economists, and so much more. We still experienced the pitfalls of international and interdisciplinary works. Different dialects, different approaches to problems, or different focuses—all these bridges had to be gapped. However, it’s those conflicts that challenge our thought routines and force us to grow. They are also where friendships start to flourish, and the island of Lesvos was the ideal background. We were able to experience a lot of its culture firsthand. From exploring small villages, the petrified forest, to Mytilene; we interacted with locals, with social workers, and with priests. All these interactions built the mosaic of our work that we tried to bring to life using digital methods.

In my mind, I’ll wander for some more time in the tranquility of the Metochi Study Centre, and I’ll never forget the creative-chaos that 30+ academics brought upon this place. All of it left a lasting impression.

Author: Julia Göke

PhD Candidate, D4H, C²DH, University of Luxembourg.

Reflecting on the Digital Humanities Summer School in Lesvos brings up a mix of vivid moments, quiet realizations, and shared discoveries. Attending as part of a group of five graduate students from Old Dominion University (ODU), I found myself immersed in a learning environment that felt both new and deeply needed. As an institution based outside Europe, ODU joined a wonderfully international and interdisciplinary cohort. Our team brought backgrounds in international studies, communication, and instructional design. While we were no strangers to working across fields, the scale and depth of diversity at the summer school were remarkable. The week offered more than academic exchange, it invited all participants into a shared process of learning – through place, people, participation, and the kind of unlearning that makes space to relearn with more clarity and care.

It also marked my own personal and professional milestone: my first experience with field research and digital humanities. The workshop’s open-ended, exploratory structure pushed me to move beyond linear expectations, setting it apart from other academic events I’ve attended. At first, I wasn’t sure how to contribute or measure my role as a newcomer, especially without predefined outcomes. But that uncertainty soon became a shared space — something we were all experiencing, and something we learned to navigate together. That shift allowed me to lean into the experience with curiosity and agency.

In our various groups, we saw how different disciplines interpret the same material through entirely different lenses. The summer school’s technically-minded participants focused on the time machine’s structure and design to determine what data to prioritize while others, like myself, began with the meaning and narrative of our time machine. These moments of misalignment sparked growth. We learned that collaboration isn’t just about tasks, it’s about negotiating values, assumptions, and ways of seeing. It’s the spirit of digital humanities.

Exploring the island’s layered narratives — from refugee landscapes to women-run businesses — alongside peers from fields like gender studies, photography, philosophy, and tech deepened my perspective and helped me grow as a researcher. Lesvos didn’t just offer new insights and amazing friends. It also reminded me why I chose academia: to stay curious, connected, and open.

Author: Guljannat Huseynli

PhD Candidate, International Studies, Old Dominion University & Storymodelers Lab.