What is the difference between digital and computational archaeology? What starts as a simple question can end in major confusion. An approach to the history of a discipline.

Author: Andrea Binsfeld

Andrea Binsfeld is an Associate Professor at the Institute of History at the University of Luxembourg. See more here.

Working interdisciplinarily is both exciting and challenging, as I’ve experienced firsthand in DTUs and various projects. Recently, my colleagues and I (we are from different disciplines) debated whether we practice digital or computational archaeology. This confusion led me to explore the history of “one of the hottest fields in the galaxy of disciplines focusing on the study of the past.” (Tanasi, 2020)

Exploring the Concept of Digital Archaeology

Digital Archaeology has generated significant debate due to the broad, vague and ambiguous concept (Lambers, 2023). It includes technologies and methods, such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), 3D modelling, virtual reality, remote sensing, image analysis, agent-based modelling, and machine learning (Evans and Daly, 2006). The field’s nature is contested: is it a distinct discipline, a methodological approach, or simply a label for using digital tools in archaeology? Its classification within academic fields is also debated: is it part of the humanities, social sciences, or archaeological science?

Scope and Impact

Digital Archaeology is described as a transformative field, influencing theoretical trends in archaeology (Tanasi, 2020). It involves using digital technologies to represent, model, and simulate the real world, understand complex human processes, and disseminating information. The practical use of computer techniques is at its forefront (Zubrow, 2006; Huggett, 2021).

Terminological Confusion

Terms like archaeological computing, archaeological informatics, computational archaeology, and virtual archaeology add to the confusion. Jeremy Huggett (2013) analyzed these terms’ usage and trends: “Computer archaeology” has been in use since the 1950s, while “digital archaeology” emerged around 1990. Erich Fisher highlights the evolving relationship between archaeology and computer science, suggesting “archaeoinformatics” – rather than computational archaeology – as the preferred term today (Fisher, 2020).

Theoretical and Epistemological Considerations

Huggett (2013) identifies an “anxiety discourse” in archaeological computing, reflecting concerns about the field’s identity, methodological rigor, and academic legitimacy. These debates illustrate broader questions about whether Digital Archaeology is merely a fashionable term or a field driven by new methods and theories.

Digital vs. Computational Archaeology

A distinction arises between Digital Archaeology and Computational Archaeology. Computational Archaeology focuses on mathematical and computational modeling and analysis of long-term human behavior, using methods like fuzzy logic, genetic algorithms, and neural networks (Barceló, 2013). It emphasizes the analytical part, including computationally intense analyses and. Computer models supporting archaeological research.

Conclusion

Digital Archaeology is a dynamic field with diverse interpretations and applications. It represents a significant shift in studying the past. While digital and computational archaeology share overlapping technologies and methods, they are not interchangeable. Digital Archaeology involves a broad application of digital tools, while Computational Archaeology focuses on analytical, computationally intense methods. The field will continue to evolve, fostering discussions about its scope, definitions, and impact.

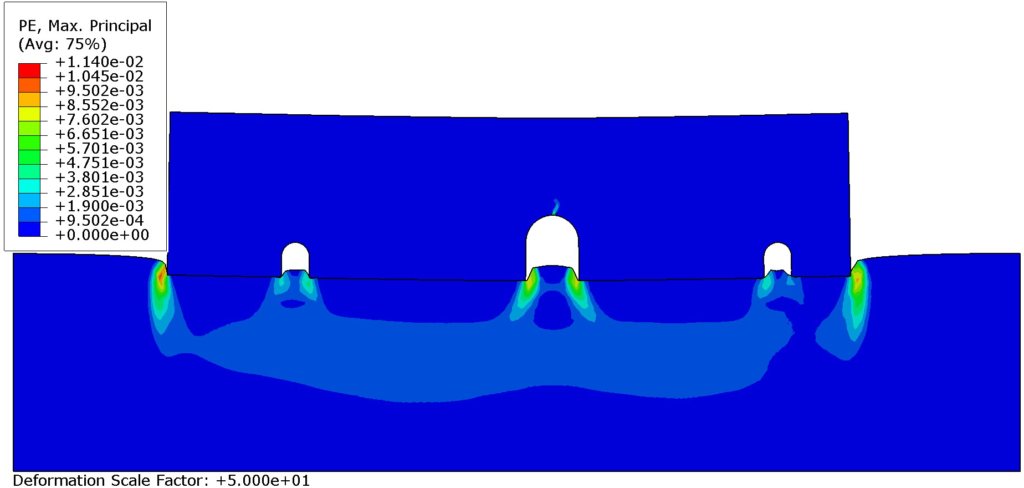

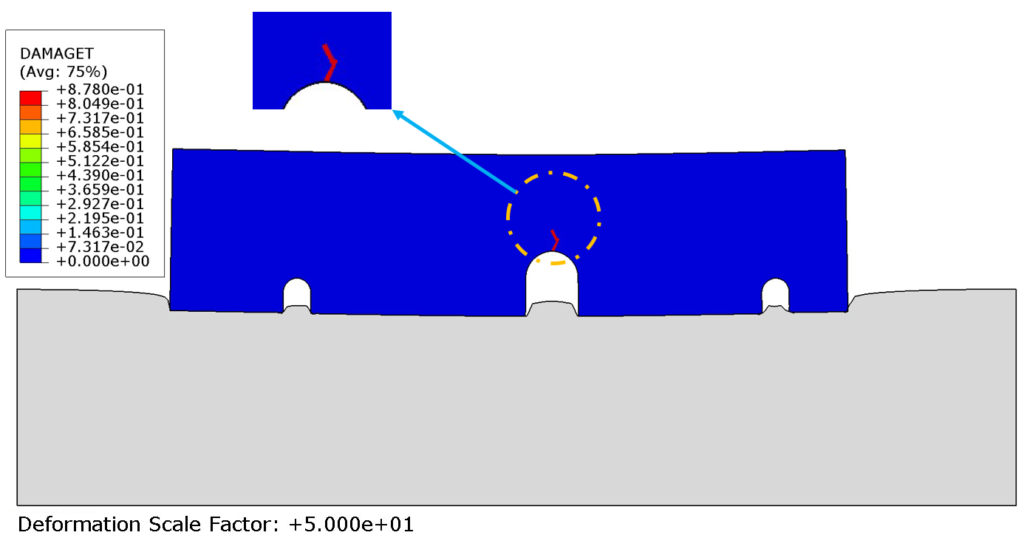

The following figures illustrate how computational methods can be used to determine the possible height of a ruined ancient building. The example shows the Assyrian palace on Tell Nebi Yunus in Mosul (Iraq). The calculation is based on data such as the foundation geometry, remaining wall thicknesses, material properties, and soil characteristics. This research is part of the ADONIS-project, funded by the IAS at the University of Luxembourg.

Bibliography

Barceló, Juan A., Computational Intelligence in Archaeology. State of the Art, in: Frischer, B., J. Webb Crawford and D. Koller (eds.), Making History Interactive. Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology (CAA). Proceedings of the 37th International Conference, Williamsburg, Virginia, United States of America, March 22-26 (BAR International Series S2079), Oxford 2010, 11-21.

Daly, Patrick; Evans, Thomas, Introduction. Archaeological theory and digital pasts, in: Evans, Thomas; Daly, Patrick, Digital Archaeology – Bridging Method and Theory. New York 2006, 3-9.

Evans, Thomas; Daly, Patrick (eds.), Digital Archaeology – Bridging Method and Theory. New York 2006.

Fisher, Erich, “Archaeoinformatics”, in: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. 2020 doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190854584.013.43.

Huggett, Jeremy, Disciplinary Issues: Challenging the Research and Practice of Computer Applications in Archaeology, in: Archaeology in the Digital Era, CAA conference 2012, Amsterdam 2013, 13-24. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt6wp7kg

Huggett, Jeremy, Archaeologies of the digital”, in: Antiquity. 95 (384), 2021, 1597–1599. doi:10.15184/aqy.2021.120. S2CID 240535798.

Kalaycı, Tuns; Lambers, Karsten; Klinkenberg, Victor (eds.), Digital Archaeology: Promises and Impasses. (Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 51), Leiden 2023. doi: 10.59641/f48820ir.

Lambers, K., Introduction: Leiden Perspectives on Digital Archaeology, in: Kalaycı, Tuns; Lambers, Karsten; Klinkenberg, Victor (eds.), Digital Archaeology: Promises and Impasses. (Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 51), Leiden 2023, 9-16. doi: 10.59641/f48820ir.

Tanasi, Davide, The Digital (within) Archaeology. Analysis of a Phenomenon, in: The Historian 82, 2020, 22-36. doi: 10.1080/00182370.2020.1723968

Zubrow, Ezra B.W., Digital Archaeology. A historical context, in: Evans, Thomas; Daly, Patrick, Digital Archaeology – Bridging Method and Theory. New York 2006, 10-31.